Smart cities won’t meet their goal of improving citizens’ quality of life unless they’re built in an open and standardised way, says Kary Främling.

(Original article from Smart Cities World)

The concept of a smart city, fuelled by data, is now rolling out across municipalities worldwide, and by providing ‘smart’ digital services, cities will become more attractive places to live for their citizens.

Yet, while open data has long been heralded as a key enabler of smart cities, in practice that data tends to be published in ways that are unusable for most data analysis purposes.

This is compounded by the fact that many companies offering smart services today are private entities with their own proprietary service platforms – a model that ultimately discourages competition for affordable services.

All of this means that we risk defeating the point of smart cities altogether. They may not enrich the lives of those who live in them as once hoped, as they will be inaccessible due to technological or even monetary barriers.

We risk defeating the point of smart cities altogether.

Can open standards offer a realistic and straightforward solution to these potential issues?

Addressing vendor lock-In

Internet of Things (IoT) systems within smart cities collect huge volumes of data but this data is often stored without the proper annotation, which can present problems further down the line.

If the technology supplier handling the data changes, for instance, then governments or local authorities could lose the value of all of that historic information.

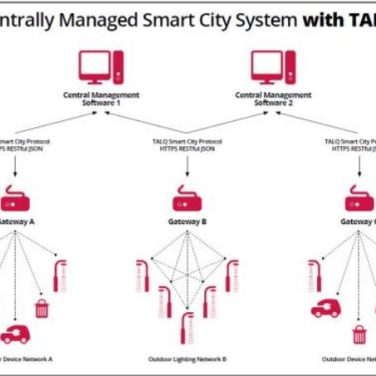

What’s more, if the APIs employed within those systems are completely proprietary – and so owned by a particular company – then it’s difficult to change systems or the service provider at all. This is all likely to result in vendor lock-in, which brings its own disadvantages such as a lack of control over pricing.

One of the real challenges when it comes to building a smart city is to get all of the systems up and running on a real-life scale, where everything works as it should without too much maintenance, and at a reasonable price.

However, once you are locked into a certain system, which then feeds into that same company’s cloud service, it is very difficult to manage budgets if the prices are raised, or to move to a cheaper supplier.

This ultimately means some governments, and therefore citizens, may be priced out of adopting smart city technologies altogether.

One practical example of this is around the use of cars in a smart city –specifically when it comes to electric vehicles (EVs) and parking spaces. If an end-user drives an EV into a city, they will need to find a free parking space, close to where they need to go, with an accessible charging point.

They don’t want to have to think about who owns the parking space. And they definitely don’t want to worry about whether that same company has provided the charging point and payment service they use, or to pay over the odds for any of these things.

They want a simple, easy-to-use service that is within budget – something that can be difficult for local authorities to achieve due to vendor lock-in.

Giving data value

Going back to basics, a piece of data has no value unless we document the value that it represents. This means tagging what unit it is measured in, when and where it was collected, and for what purpose.

Even when data is annotated, this is not always done to the same standard for each piece of data, which means that it is just as difficult to access. Again, if it is handed over to another company it becomes even less valuable, resulting in ‘data lock-in’.

A piece of data has no value unless we document the value that it represents.

For example, when new owners take control of a building that has previously been run by another facilities management company, they have to reinstall a huge number of sensors and information systems. None of the collected data is then transferred, meaning that any historical data is lost and they must start all over again.

A solution to this can be found via open standards. For instance, the Open Data Format is one way in which entire data lakes can be stored and annotated and then be used by other systems, citizens or decision-makers.

By addressing this issue head-on, we will increase the value of data, resulting in improved smart services that will ultimately be more beneficial to those using them.

Prioritising open standards

For years, open data has been seen as a primary enabler of smart city technologies. Open standards, such as The Open Messaging Interface (O-MI) and Open Data Format (O-DF), provide a framework to make data exploitable for analysis and machine learning purposes.

The result of such analysis and machine learning should be new or improved smart services that can be used by other systems, citizens or decision-makers. The recent Version 2 of O-MI and O-DF include new functionalities that extend data annotation to smart services, and that can be represented in standardised ways. These technologies have been used extensively in several European cities in the context of the bIoTope EU project.

This project, run with The Open Group, industry players, and academic institutions, comprises a series of cross-domain smart city pilot projects. These smart pilots have been rolled out in Brussels, Lyon, Helsinki, Melbourne and Saint Petersburg to date and will provide proofs-of-concept for applications such as smart parking, the safety of school children in traffic, climate control in cities, smart waste collection and vendor-neutral electric vehicle charging.

The end goal of the bIoTope project is to showcase the benefits of utilising the IoT, such as greater interoperability between smart city systems. In addition, it will provide a framework for privacy and security to guarantee responsible use of data on the IoT.

Fostering innovation

With open standards in place, authorities can still remain competitive with the service provisions they offer and avoid vendor lock-in, while also creating and maintaining a sustainable business ecosystem.

The future of our smart cities rests on the free flow of data and the adoption of open standards.

The future of our smart cities rests on the free flow of data and the adoption of these standards, and we are already seeing this in practice.

Ultimately, the technology behind a smart city is intended to help improve citizens’ quality of life – whether that be through better air quality or increased mobility options, to name just two of the potential benefits. But this won’t happen without the use of open standards.

Those in charge of managing our smart cities should look to build a secure, open and standardised system for the IoT network that they operate, and ensure that it ultimately benefits the people that it serves.